Considering the risks and opportunities of responsible investments in the world’s second-largest equity market.

After the decision to include A-shares in the MSCI indices in 2017, Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges, together with MSCI, organised a high-level seminar. Karine Hirn from East Capital participated alongside MSCI's CEO, the top management of the exchanges, the regulator, the largest Chinese and foreign brokers, domestic and international investors.

China is increasingly on the radar screens of global investors, and for understandable reasons. First up, it is the only major global economy that ended 2020 not in recession (+2.3%), and without any major rescue package. In addition to this remarkable macroeconomic achievement, China is still poised for a robust rebound in growth (+8.2% in 2021), driven by supportive policies and the improving confidence of corporates and households. The long-term picture also looks good, as China aims to further double its GDP over the next 15 years, implying a 4.7% growth rate per annum. While geopolitical tensions have not vanished, and will persist in the future, the US-China relationship has become more stable and predictable with the accession of the new US administration.

Of the several instruments and asset classes available to investors for gaining exposure to China, the domestic equities market (“A-shares”) is particularly attractive to stock pickers such as East Capital. Despite their outperformance in 2020, gaining 38.6%, Chinese A-shares remain reasonably valued, at 18x P/E 2021E, with developed markets at 22x and the emerging markets index at 16x.

As ESG investing has reached a tipping point around the world in the wake of the pandemic, investors often ask us (given our experience of investing in Shanghai and Shenzhen-listed stocks for several years) our views on the current ESG standards and how we approach responsible investing in this market, which is major by size, but still unexplored and often misunderstood by mainstream investors.

Opening up and reforms

When we opened our office in Shanghai in 2010, we quickly identified A-shares as an appealing opportunity for active managers. This market is, like most emerging markets we have been working on in Eastern Europe for more than two decades, young (less than 30 years old). Companies listed in the mainland markets offer diversified exposure to domestic consumption and investment themes, strong growth and exciting risk-return profiles for stock-pickers, and with a low correlation to other markets. We launched our first A-shares strategy in 2013, after securing the first ever QFII license given to an asset manager in Northern Europe. Since then, the market has opened up further, and thanks to a very determined reform program, access is now much easier through the Stock Connect programs, which allow foreign investors to trade A-share names listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen, without any specific license and quota, which was not the case in the past. The decision by MSCI in 2017 was a major step that significantly added to investors’ interest and has since driven a gradual institutionalisation of these markets.

The specifics of the world's second largest market

The A-shares market has more than 4,500 companies, split roughly 50-50 between Shanghai and Shenzhen. With a market capitalization of USD 11 trillion, it is now the second-largest market in the world. Unlike in most emerging markets, foreign investors are only a minority here, holding just 3.8% of the market. For technical and regulatory reasons, the index provider, MSCI, now gives it a weight of only 5% in the MSCI Emerging Markets index. But over time, A shares could represent nearly 20%. This huge market is very dynamic, with daily liquidity of over USD 100bn. The share of retail investors went from 95% of free-float when the market first opened in the nineties, to 70% in 2010, and is now 50%1.

In parallel with the ongoing institutionalisation of the market, we have observed an improvement in governance standards, even if the market as such often finds itself at the bottom of the rankings of international rating agencies. An essential reason for the weakness in these rankings is the lack of information provided by companies. The level of disclosure on ESG tends to be relatively low in emerging markets, and coverage by ESG data providers is even lower in a market like A-shares, which is one of the reasons we have developed our own scorecards. Another reason is that many ESG ratings primarily relate to ESG policies rather than practices, which again favours larger companies and those in developed markets that have a better understanding of what is expected from them and more resources to dedicate to meeting these expectations.

The reform of the Corporate Governance Code in 2018 (the first reform since the Code was adopted in 2002) however, represents progress on implementing recommendations (but no obligation) for disclosure on environmental considerations, societal responsibilities and investor protection. But disclosure is still far from best-in-class by international standards. Today, only around 20% of listed companies publish an ESG report2.

Responsible investment practices are becoming more common. There are now 51 Chinese signatories to the UN PRI (Principles for Responsible Investment), a remarkable step forward, as there were only 7 in 2017.

Does china offer specific governance challenges compared to other emerging markets?

Governance is the area where there is most work to be done in China. We think that one of the reasons is the standards and the role of boards. In Eastern Europe, which was our initial market, there is a culture of having independent directors that are accountable, and boards that work. Not all of them work perfectly, and the poorer quality ones are probably those of companies we wouldn’t want to invest in – but shareholders can work with boards, communicate with directors and help nominate directors.

Obviously, it helps that in Eastern Europe we are a very large and influential investor, whereas in China we have less clout – but even the large asset managers with extensive resources here say that they find it difficult to work with boards.

Besides, independent directors are often academics or semi-retired people, who probably are competent, but are not likely to be the ones standing up for the rights of minority shareholders. The issue of board quality is not unique to Chinese domestic markets; even Hong Kong listed companies count so-called “independent” directors who have been holding the job for 15 years, which for us, is a red flag, as we do not think someone can be truly independent if they have been remunerated for so long by the same company.

As a shareholder, we prefer dialogue with management teams to move matters forward. Auditors, and specifically auditors’ tenures – which can be very long while we consider that auditors should change after 7 to 10 years - tend to be a recurring topic in our dialogue with companies. Capital allocation practices, which are a major corporate governance issue in our proprietary analysis, are another recurrent topic, as they are not always of the quality we would expect, especially in state-owned enterprises. For instance, it is not uncommon to find companies with excess cash that might be better returned to shareholders or used for share-buybacks than spent on low-return cash management alternatives. SOE reforms and equity-based incentives are also a topic we are paying specific attention to, as they can have a major impact (positive or negative) on the operational excellence of a company.

Voter participation in China is also relatively low (only 26% of minority shares3), although it is improving. This is not only the fault of investors though, as sometimes, casting a vote is technically complicated. One real estate company had 25 EGMs during one year because it was in their articles of association that any new transaction required approval by the board.

"Women not holdning up half the sky" in the board rooms

Gender diversity is dire almost everywhere, and generally worse in emerging markets than in developed markets. Even by those standards, though, China is weak. Progress is being made, but still only 13% of all directors are women, which is hard to understand because there are a lot of very competent women involved in the management of Chinese companies. Chinese female CEOs, on the other hand, represent 6% of CEOs (compared to 4.8% worldwide)4.

The largest company by market capitalisation in the world with an all-male board is Chinese. It is Kweichow Moutai, producer of a premium white liquor currently retailing at around Rmb3,000 per bottle. It is also the biggest company in the A-shares market. It should be noted though that Hong Kong-listed Chinese companies are actually on average worse than Chinese A-shares companies. We are not only talking about traditional industries and incumbent companies. The issue is even prevalent in the tech sector; Xiaomi does not have any female directors and Tencent only got its first in 2019, after 15 years of all-male board meetings. Nearly a third of all Chinese companies in the MSCI Index have all-male boards.

Social risks

There are obviously serious concerns related to human rights and labour law in China, although overall we note that health and safety standards and rights of workers are relatively high and well-protected compared to some other emerging markets, at least in the manufacturing industry. This is probably partly due to the fact that as the demographic divide in China is disappearing, industries that are still labour intensive need to have better terms for workers to attract and retain staff.

Interestingly, while there have been notable improvements in old economy industries, staff participating and contributing to the boom of the new economy, i.e. services and tech, are probably less well-off in terms of work conditions. The controversial “996” work culture, referring to working from 9am to 9pm six days a week, is very common, and obviously not sustainable. Anecdotally, during our visits to Chinese companies, especially those operating in rapidly-growing industries such as Internet and tech, we often notice foldable beds near employee desks, as employees frequently have to spend nights in the office working on urgent projects with tight deadlines. We even saw staff toilets that are specifically designed for people not to overextend their visits surfing on their mobile phones.

Material risks for investors on the social side pertain to issues like data privacy and data ownership, which are a concern for most companies and obviously even more so for Internet and tech companies. Predatory practices in B2C industries and consumer right protection standards in general are lagging behind.

Worst polluter on the planet...

Climate change is undeniably a key topic for investors and companies around the world, and obviously for China as well, as the world’s largest GHG emitter. However, here, it is also strongly intertwined with environmental pollution. It’s no secret that the fast growth of the last 30 years has come at a heavy cost for the population in terms of environment and for biodiversity, for which we have plenty of anecdotal evidence (foul air, red rivers, painted grass) after having lived in China and travelled across the countries visiting companies and industrial sites.

Since 2016, high-polluting companies have been required to disclose key pollutant emissions, but disclosure in general remains very weak. Together with now 100 investors globally, we have been supporting the CDP disclosure campaign for the second year in a row, and last year targeted 22 companies in China. Both climate transition risks and physical risks (water stress in the north, flood risks for coastal megalopolises, landslides) are expected to come higher up on the agenda for investors and companies alike. China is about to launch its national carbon market, and its recently-announced bold carbonisation plan (carbon neutrality by 2060) has sparked huge interest in the topic and outstanding performances from companies operating in the renewables sector.

We have seen more Chinese investors joining Climate Action 100, an investor-led initiative to engage systemically important GHG emitters and drive the clean energy transition. We are very active ourselves in Russia, co-leading three engagements, but not yet in China, as we are not shareholders in any of the Chinese companies on the list. We have noted that so far, there has been quicker progress and more achievements in Europe than in China, with specific challenges in engaging with Chinese companies on these topics, and possibly less experience of collaborative engagement in the region compared to Europe.

Peter Elam Håkansson (Partner & CIO), Karine Hirn (Partner & CSO) and Dmitriy Vlasov (Portfolio Advisor) in Xi'an, visiting Longi Green Energy, the world’s largest solar company by market value.

...But a greentech champion

National priorities concerning the fight against pollution for several years, and now decarbonisation, have led to a rotation of investments into green sectors, and a strengthening of the regulatory framework for polluters.

If you look at the emerging markets investment universe, China is really the only market that has been producing interesting companies in the green economy space at scale. Whether it’s cleantech, renewable energy or electric vehicles, there isn’t really any better alternative to China.

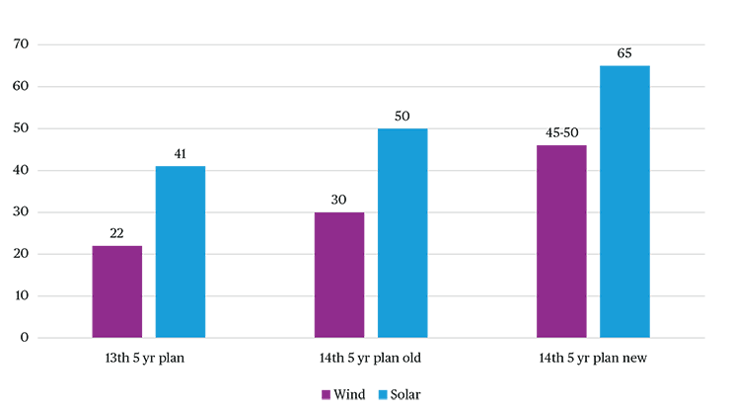

Last September, President Xi unexpectedly pledged to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 and peak CO2 emissions before 2030. According to UBS, this ambitious goal would require raising the primary energy mix target from renewables to 25% (from the current level of 15%) by 2030 to achieve installed renewables capacity of above 1,200 GW. In the near term, this policy objective implies a substantial increase in installation targets for the power generated from renewables. We estimate that solar installations would average 65 GW, while wind installations are likely to achieve above 45 GW per annum – substantial increases from the levels achieved over the 2015-2020 period.

Figure 1. Annual solar and wind installations in China, in GW

These aggressive targets are achievable, in our view, given near cost parity for renewables, especially for solar, as compared to fossil fuel. Due to economies of scale and improving efficiency of products, Chinese companies now control above 60% of the solar supply chain. In solar-grade polysilicon, for example, China accounts for over 70% of global production, compared to only 25% in 2012. Leading Chinese solar companies are well positioned to benefit from surging global demand for solar panels, as more countries make irreversible commitments to clean power. Longer term, annual installations or renewables power generation would need to be above 200 GW for China to deliver on its commitment to decarbonise its economy. Few other sectors represent such a long-term growth trajectory, and Chinese companies like Longi Green Energy are at the centre of this. With market capitalisation of USD 70bn, Longi Green Energy is the world’s largest solar company by market value. The company is the global leader in solar wafers, with a 30% market share.

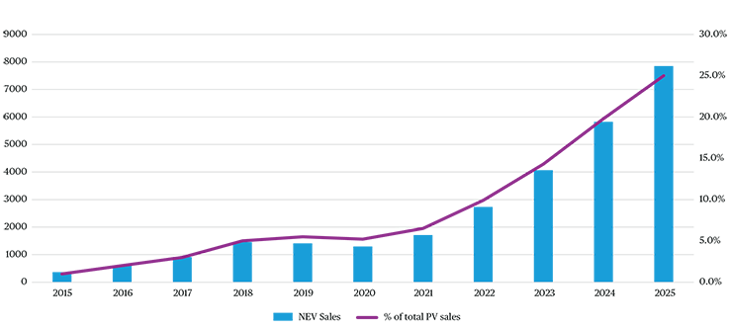

China’s leadership in the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) is also undisputed. Transportation contributes 10% of China’s carbon emissions, and as such, the Chinese government has been aggressively promoting the development of the homegrown EV industry. Last year, sales of EVs in China reached 1.25 million, a 14.6% y-o-y increase. While overall car sales declined by 6%. Due to advancements in technology, especially the improvement of batteries, EVs are expected to reach cost parity with internal combustion engine cars by 2024. This will accelerate the adoption of EV cars in China and globally. Last year, EVs accounted for 6% of total car sales in China, and we expect the percentage of EVs to increase to more than 25% in 2025 and to almost 50% of total car sales by 2030. Globally, EV penetration is expected to reach 40% by 2030. Similarly to renewables, Chinese companies now play a leading role in multiple parts of the EV supply chain. CATL, one of the battery suppliers to Tesla, is the largest EV battery manufacturer globally, with a market capitalisation of nearly USD 150 bn. According to UBS analysts, the company has one of the lowest production costs for batteries in the world . Its third-generation NCM 811 battery pack and cell costs declined to USD 120/kWh and USD 99/kWh respectively.

Figure 2. NEV PV sales and % of total PV sales

Looking ahead

Chinese issuers clearly have a long way to go on sustainability, even though they are making great efforts and the regulators are stepping up the pressure. The way companies report on their ESG efforts or contributions to the SDGs is still in the very early stages. But like many emerging markets, China has an amazing capacity to act fast and change in a way that the old-developed world often cannot.

In China so far there has been more push than pull on ESG – most of the movement has come from regulators rather than investors. But it is encouraging to see more foreign institutional asset managers entering this market. Even more positive and important, as with all the emerging markets we invest in, is to observe that local asset managers start focusing on ESG issues. We wish to see more long-term asset owners arrive on the scene. So far, only two Chinese asset owners have signed up to the PRI.

Part of our investment case for China is that the nature of the investor base is changing. For a long time, Chinese domestic markets were dominated by domestic investors. But now that markets are gradually opening up, foreign institutional investors are becoming increasingly influential, and for most of them, ESG is clearly a priority. That in turn is changing the way that both Chinese corporates and investors think about the topic.

___________

1 MSCI research

2 ZD Proxy Shareholder Services

3 Fidelity China, ZD Proxy Shareholder Services

4 MSCI Women on Board Progress Report 2020